A brief background to the title of the book, including pronunciation of ‘wouivre’

The Power of the Wouivre, as a title, was set in stone long before the book was even out of its first draft. The concept of wouivre has fascinated me ever since I came across the word in a book many, many years ago. The idea for the novel came into being long before the internet was as prevalent as it is today and, even now, 20 years on, there is very little of substance written about the wouivre online. However, from having beta readers ask how to pronounce it, to people thinking that I made the word up, I wanted to talk a little bit about the wouivre.

First, let’s tackle the pronunciation. The word ‘wouivre’ is one with much controversy of pronunciation and nowadays the internet will pronounce it many ways, most of which I would decree incorrect! I would pronounce it WEE-VRE, as it comes directly from the the French word ‘vouivre’ pronounced here. Interestingly, the medieval English equivalent ‘wyvern’ was also originally pronounced WEE-VERN before modern English decided to change the EE to an AI (I) sound!

But what is the wouivre? As a physical being, it is somewhere between a dragon and a snake. In English, we would probably be more familiar with the word wyvern, which is a two-legged dragon, but the wouivre can be depicted both with two legs and wings, or as a serpent with dragon head (the French vouivre is often depicted as a winged snake with ruby eye that guards valuable treasure). On an analogical level, the word wouivre can describe anything that ‘snakes’ or glides through the Earth such as bodies of water or electrical currents. And as a spiritual extension of this gliding water, it is a term encompassing the telleric, female energy of the Earth itself.

Guelphs and Ghibellines

I first came across the term when researching the Battle of Montaperti, a very famous battle for anyone familiar with Italian history (and specifically Tuscan, since Italy was not a unified nation until 1861, when it became the Kingdom of Italy). For those not familiar, the Battle of Montaperti was the bloodiest battle of the Italian Middle Ages, which, in a land and time known for extreme bloodshed, and mindless vengeance, is really saying something! Montaperti was the culmination of a longstanding rivalry between Siena and Florence, and the catalyst for further battles for Tuscan supremacy between the two city states.

But the animosity was not just geographic; it had its roots in politics. At the time, Germany ruled much of Italy, and many of the states (that we now know as regions of Italy) were either in support of the German Emperor or the Pope. The Imperial supporters were known as Ghibelline and those in favour of the pope were called Guelph. These parties, or factions, were also divided on a class level, where Ghibelline came to stand for nobility, and Guelph, for those from the middle, merchant, class. Thus, there was some cross-over where papal supporters might end up fighting for the Ghibellines and some noblemen might be on the side of the Guelphs. Equally, while one city might predominantly hail as Guelph or Ghibelline, within that city would be supporters of either faction. In fact, many cities were perpetually living in a state of civil war at this time.

This background is important and relevant to the story of The Power of the Wouivre, but also to the symbol of the wouivre itself. Many of the Ghibelline emblems would have the wouivre, in one form or another, on their standards (“Tuscan Armies – Sienese and Florentines at Montaperti” by Roberto Marchionni). In fact, it was such a well-known symbol that it even became adopted by many Guelphs who would show the wouivre being subjugated by one of their own symbolic animals such as a griffin or eagle.

Mythology and Spirituality

Looking at the spiritual meaning of wouivre, it is interesting to note that the creatures adopted by the Guelph league to subjugate the wouivre on their banners, have a traditionally male energy, whilst the wouivre, as already mentioned, was considered a strong female energy. As we are talking about an era that was quite definitely, patriarchal, it is for you to decide if this is coincidence or has some deeper, spiritual meaning. Certainly, though, we can build on the femininity of the wouivre. If we look at the French word ‘vouivre’, this is predominantly depicted in mythology as a female, often with the ability to transform into an actual woman.

This is further elaborated in the analogical and spiritual interpretations of the word as water, or as the energy of the land itself – the Earth – also often referred to as Mother Earth. In terms of the four elements, it is true that fire and air are considered male, while earth and water are associated with female energy. This natural energy is prevalent in eastern cultures. In hinduism, the wouivre would be synonymous with ‘kundalini’ – the goddess energy in the form of a coiled snake, that lies at the base of the spine. In China, this life force that has the potential to flow through all of us, is known as ‘chi’. When the serpent is depicted swallowing its own tail this is representative of the continual nature of the Earth spinning on its axis, rotating through each season continuously. This circular serpent is called ‘ouroboros’.

Ley lines

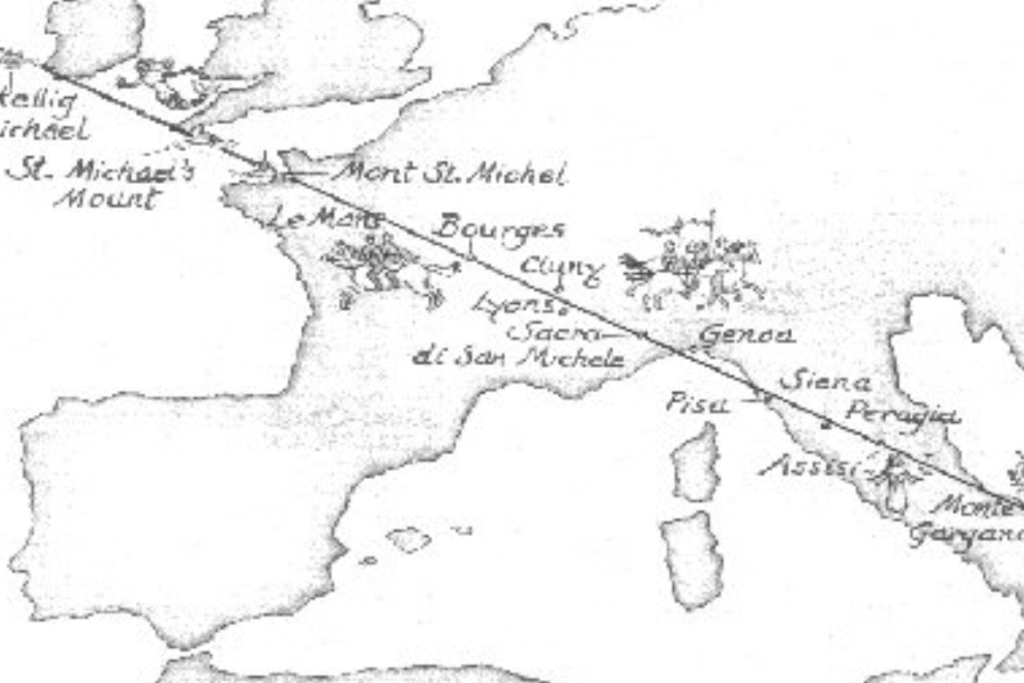

The relationship of wouivre to the Earth can also be explored through the discussion of ley lines. A ley line is an imaginary, or invisible, straight line (depending on your perspective) that connects certain key, spiritual sites throughout the world, (within around a 10 mile margin of error). One such ley line runs from Skellig Michael in Ireland, through St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall, Mont St Michel, Normandy, San Michele di Monte Gargano, Foggia, and beyond to Athens and ancient Greece. As the line passes through Tuscany, it crosses almost between Florence and Siena. (It also crosses almost straight through Lyon too which is one of the reasons I picked that French city for the site of my second book).

It is no coincidence that many of the important sites on the line are churches or monasteries dedicated to the archangel St Michael. Indeed around Siena alone, are many smaller churches and chapels also dedicated to St Michael. Experienced dowsers have discovered telluric currents along this line, and in particular at the religious sites along it. It is believed that Christians built their monuments in these locations to channel the natural energy of the Earth, creating vast structures, often on hilltops, that reached high into the sky, to carry the energy to God in the heavens.

The image of St Michael is often depicted killing, or subjugating, the dragon. Traditionally this has been interpreted as slaying the devil, but there is another possibility that, in those locations, the archangel was meant to be taming the natural energies of the Earth to direct them up to Heaven. Throughout history, pilgrims have made arduous journeys to these sacred places. In the Middle Ages, the Knights Templar may well have been aware of these energies and the importance of protecting them. There is even some speculation that knowledge of this power may have been the Holy Grail itself!

In the Power of the Wouivre, the wouivre itself is nothing more than a small terracotta amulet. But in that one disc is encompassed all of the above, to provide a thread that snakes, like the wouivre itself, through the very essence of the story, tying times, plots and characters into one remarkable tale that defies time and space, whilst being firmly grounded in historical fact. You can read a sample here

(If you want to learn more about the wouivre energies, and the St Michael’s ley line in particular, The Dance of the Dragon by Paul Broadhurst and Hamish Miller was an invaluable resource to me).